We often think that a random headache or brain fog is temporary. There is, however, a source that causes the temporary malady. One should not take these events lightly, especially when they tend to recur. In this case, one should become hyperalert. For some time now, we need to not trust that all manufacturers are trustworthy. Trustworthiness in the chemical manufacturing industry is complex, featuring a mix of highly-regulated, specialized, and reliable firms alongside instances of corporate negligence and, in some cases, deliberate suppression of health data.

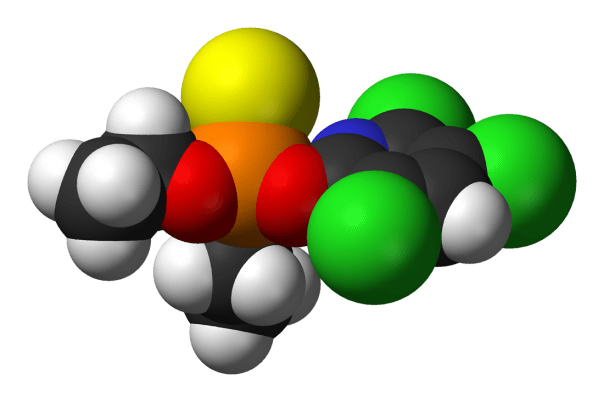

The main “ingredient” in chlorpyrifos products is the technical‑grade active substance (chlorpyrifos technical), which is manufactured and supplied in bulk primarily by large agrochemical producers in China and India, with some legacy production from multinationals such as Dow/Corteva and others.

How chlorpyrifos is sourced

- Chlorpyrifos was originally developed and first produced commercially by Dow Chemical (later Dow AgroSciences, now part of Corteva), which for decades was one of the principal global manufacturers supplying technical‑grade chlorpyrifos to formulators.

- Over time, production expanded globally; current reports note that China and India are now two of the biggest producers of chlorpyrifos, with large volumes exported as technical material to other countries where it is formulated into end‑use products.

- A risk‑profile and NGO country‑situation reports list Dow AgroSciences (USA and UK), Makhteshim (Israel, now part of ADAMA), FMC (USA), and Cheminova (Denmark, now also under FMC/ADAMA ownership) among approved or recognized sources for import of chlorpyrifos technical into markets such as India.

- In the current market, there are hundreds of suppliers and distributors of chlorpyrifos products globally, but most do not synthesize the molecule themselves; instead, they buy chlorpyrifos technical (the main active ingredient) from large technical‑grade manufacturers—predominantly in China and India—and then formulate and package it (e.g., 50% EC, 50% WP, granules) for sale.

If you are looking for “who sources what from whom” in a specific country or for a particular brand (e.g., which technical supplier a given U.S. registrant uses), that usually requires looking at that company’s registration dossiers, import approvals, or trade data, which can sometimes be pulled from regulatory filings or subscription market reports rather than public summary pages.

What are the main raw materials used to synthesize chlorpyrifos?

Chlorpyrifos is built from a chlorinated pyridine ring and a diethylthiophosphate group, so the key raw materials are the precursors to those two pieces.

Core starting materials (conceptual)

In standard industrial routes, the main raw materials are:

- A substituted pyridine starting material (commonly 3‑methylpyridine / 3‑picoline or related pyridine derivatives), which is then chlorinated and transformed into 3,5,6‑trichloro‑2‑pyridinol (often called TCP).

- A phosphorus oxychloride–type reagent that ends up as O,O‑diethylphosphorochloridothioate (the diethylthiophosphate chloride used to introduce the organophosphate side).

- Ethanol (or another C2 alcohol source) to form the diethyl ester part of the thiophosphate.

- Chlorinating agents (such as chlorine or other chlorinating systems) used to introduce the three chlorine atoms onto the pyridine ring.

- Sulfur/thiation reagents (or sulfur dichloride / related sulfur chlorides in some routes) to convert a phosphorochloridate into the corresponding phosphorochloridothioate (P=S).

- Bases and caustic alkali (e.g., sodium hydroxide, sodium carbonate) to generate the phenoxide (pyridinol salt) and to neutralize HCl during coupling.

Immediate precursors to technical chlorpyrifos

Focusing on the last synthetic step that actually yields chlorpyrifos, the two “main” raw materials are usually:

- 3,5,6‑trichloro‑2‑pyridinol (or its sodium salt).

- O,O‑diethylphosphorochloridothioate (diethyl thiophosphoryl chloride).

These are reacted under basic conditions so that the pyridinol (as its sodium salt) attacks the phosphorus center, displacing chloride and forming chlorpyrifos.

How is 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol produced

Industrial production of 3,5,6‑trichloro‑2‑pyridinol (TCP) uses chlorinated pyridine routes or “chloroacrylonitrile” routes, but all converge on building and then selectively chlorinating a pyridinol ring.

Classic Dow-type (acrylonitrile / trichloroacetyl chloride) route

A widely cited process (Dow patent) prepares TCP from simple chlorinated C2 building blocks:

- Trichloroacetyl chloride is reacted with acrylonitrile to form 2,2,4‑trichloro‑4‑cyanobutanoyl chloride (an adduct).

- This adduct is cyclized under acidic conditions to give a dihydropyridone (3,3,5,6‑tetrachloro‑3,4‑dihydropyridin‑2‑one).

- The dihydropyridone is then aromatized (dehydrogenated) to 3,5,6‑trichloropyridin‑2‑ol (TCP), and the product is isolated by standard workup (acidification, phase separation, solvent removal).

In this route, the effective “raw materials” for TCP are trichloroacetyl chloride, acrylonitrile, an acid catalyst, and solvent.

Alternative chlorination / demethoxylation routes

Other patented processes start from partially chlorinated pyridines and then introduce additional chlorine atoms:

- 2‑chloro‑6‑methoxypyridine is first subjected to acid‑catalyzed ether cleavage (with concentrated HCl) to give 6‑chloro‑1H‑pyridin‑2‑one.

- Without isolation, an aqueous carboxylic acid (e.g., acetic acid) is added and chlorine gas is passed through the headspace, chlorinating the ring to 3,5,6‑trichloro‑1H‑pyridin‑2‑one (i.e., TCP).

- A separate family of routes chlorinate 2,3,5,6‑tetrachloropyridine under basic conditions (NaOH, phase‑transfer catalyst) and then partially hydrolyze to give 3,5,6‑trichloro‑2‑pyridinol.

These approaches use 2‑chloro‑6‑methoxypyridine or 2,3,5,6‑tetrachloropyridine plus hydrochloric acid, carboxylic acid, chlorine gas, sodium hydroxide, water, and a phase‑transfer catalyst (e.g., TBAB).

Summary of main intermediates

Across commercial routes, TCP is typically obtained via:

- Formation of a chlorinated dihydropyridone intermediate from trichloroacetyl chloride and acrylonitrile, then cyclization and aromatization.

- Or chlorination/hydrolysis of pre‑formed chloropyridine derivatives such as 6‑chloro‑1H‑pyridin‑2‑one or 2,3,5,6‑tetrachloropyridine.

How is TCP purified after synthesis

After synthesis, 3,5,6‑trichloro‑2‑pyridinol (TCP) is typically purified by phase separation, acid–base workup, and one or more crystallization/drying steps.

Typical industrial workup

- The crude reaction mixture is first neutralized or adjusted to a basic pH (often with NaOH or KOH), which converts TCP to its water‑soluble sodium or potassium salt and separates organic and aqueous phases; the solid catalyst (if used) is filtered off.

- The aqueous phase containing TCP salt is then acidified (e.g., with sulfuric acid) to around pH 2, which precipitates TCP as a solid that can be isolated by filtration.

- The wet cake is washed with water to remove inorganic salts and residual acids/bases, then dried (tray dryer, vacuum dryer, or similar) to yield technical‑grade TCP.

Crystallization and polishing

- For higher purity, TCP (or its sodium salt) may be recrystallized: the crude solid is dissolved in hot water or a suitable solvent, then the solution is slowly cooled so TCP crystallizes; the crystals are collected by filtration and dried.

- Some processes include solvent extraction (e.g., methanol/ethanol extraction of the sodium salt followed by solvent distillation) to remove organic impurities before final drying.

In practice, a producer will tune pH, temperature, and solvent choice so TCP precipitates cleanly, filters easily, and reaches the purity needed for downstream chlorpyrifos manufacture.

Febreze, the “Scent Reward”

Once a failed product, it became a household staple by marketers shirting the focus from removing odor to providing a satisfying “scent reward.” That’s to say, consumers are taught to buy emotional, sensory experiences over technical, functional benefits.

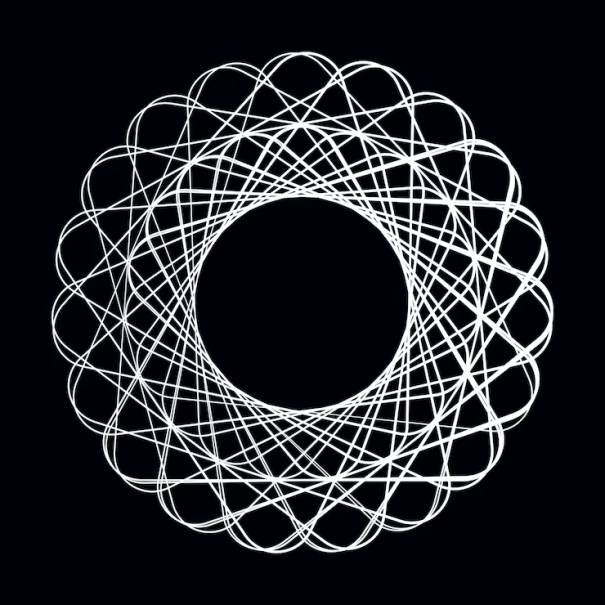

The “torus” or donut‑shaped molecule in Febreze is a modified cyclodextrin, most commonly hydroxypropyl‑β‑cyclodextrin (HPβCD), which is a ring made of sugar units derived from starch (typically corn).

However, the main ingredient, hydroxypropyl‑β‑cyclodextrin (HPβCD), as a compound, one must consider this: toxicity level + route = condition of patient. It is toxic. Though it is considered low in toxicity when used at “safe levels” (an unknown factor), it is known to tress the kidneys and can accumulate in patients with kidney impairments. Under some extreme exposures, it can cause renal toxicity, including kidney tubular damage, liver changes, and ototoxicity (hearing changes).

What the self-regulating torus molecule is

Chemical makeup at a simple level

At the level of “what chemicals” form the torus:

- Each ring unit is a glucose molecule (formula C6H12O6), so unmodified β‑cyclodextrin is essentially seven glucoses linked together (overall formula C42H70O35).

- The hydroxypropyl modification adds small hydroxypropyl groups (–CH2–CHOH–CH3) onto some of the hydroxyl (–OH) sites on those glucose units; the exact number and positions vary, so HPβCD is a mixture of similar molecules rather than one single, fixed molecular formula.

How the torus behaves chemically

- The outside of the ring is rich in hydroxyl (–OH) groups, making it hydrophilic and water‑soluble.

- The inner cavity is relatively hydrophobic, so it can host (form “inclusion complexes” with) non‑polar odor molecules; this is what lets the torus “trap” smells.

If what you want next is the full ingredient list around that torus (surfactants, preservatives, fragrance, etc., in a specific Febreze product line), I can walk through those as well.

Beta‑cyclodextrin traps odor molecules by forming a host–guest inclusion complex in its ring‑shaped structure, which physically “cages” the odor so it can no longer reach your nose.

Structure and polarity

- Beta‑cyclodextrin is a torus (donut‑shaped) ring of glucose units with a hydrophilic exterior and a relatively hydrophobic inner cavity.

- Many odor molecules are nonpolar or weakly polar and “prefer” the hydrophobic interior over water or air, so they spontaneously move into the cavity.

Host–guest inclusion complex

- When an odor molecule enters the cavity, weak intermolecular forces (van der Waals interactions, hydrophobic effect, sometimes hydrogen bonding) stabilize it inside the ring; this is called an inclusion complex.

- The binding is not a new covalent bond; it is a reversible physical association where the cyclodextrin is the host and the odor molecule is the guest.

Effect on odor and volatility

- Encapsulated odor molecules are shielded from the surrounding air and water, which greatly reduces their effective volatility (tendency to escape as vapor).

- Because far fewer odor molecules escape into the air to reach olfactory receptors, the perceived smell drops, even though the molecules are still present but “hidden” inside the beta‑cyclodextrin cages.

Role of water in sprays like Febreze

- In a spray, water first dissolves or solubilizes airborne or surface odors, bringing them into contact with dissolved beta‑cyclodextrin.

- Once contact occurs, the malodor molecules partition into the hydrophobic cavities, forming many tiny inclusion complexes that remain in the liquid phase or on surfaces instead of in the air.

About ingredients and regulations – the loophole

- Products like Febreze must comply with local chemical and safety regulations wherever they’re sold. Different regions have various safety standards (for example, EU’s REACH chemical regulations), but that doesn’t mean a ban — it means meeting rules before being sold. Safety data sheets for Febreze variants show compliance with EU regulations.

- There’s no credible evidence that specific Febreze products are formally banned by major countries or regions (e.g., EU, Canada, Japan, Australia) due to ingredients — they simply go through normal regulatory review.

[ SOURCES – AI ]

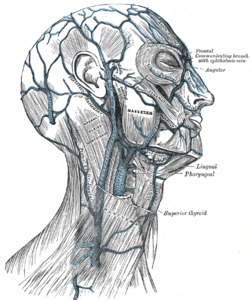

Since the fragrance molecule within the Febreze torus molecule is proprietary, the public can never know the toxicity of the P&G chemicals used to emit its scent repeatedly. Thus, this is a problem for persons experiencing heath effects that are noted in the health condition known as MCS (Multiple Chemical Sensitivities), which is recognized by several countries (Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Japan, Luxenbourg, and Spain). However, in some persons with MCS, they experience almost instantly the swelling of the layers of tissues and epicranial aponeurosis (tendon-like structure). This inflammation is often debilitating and can manifest in other organ areas.

Briefly, when it comes to the scalp, it has five layers: (1) skin; (2) dense connective tissue (it contains blood vessels); (3) epicranial aponeurosis; (4) the loose areolar connective tissue (it separates the percosteum of the skull from the epicranial aponeurosis; and (5) the periosteum (the outer layer of the skull bones. It becomes continuous with the endosteum at the suture lines). And the blook travels from the scalp. Here is how:

“The blood from the scalp travels through a complex network of arteries and veins. The superficial temporal artery is a key artery that supplies blood to the scalp and face. It branches off from the external carotid artery and has multiple branches that take blood to the forehead’s muscles and skin. The superficial temporal veins drain blood from the scalp and face, with the angular vein being a terminal branch that drains blood from the scalp to the neck.

“The internal jugular veins are responsible for draining deoxygenated blood from the skull and brain, and the jugular veins return deoxygenated blood to the heart. The dural venous sinuses collect blood from the brain and transport it to the internal jugular veins, which then drain into the subclavian veins and the external jugular veins. The supraorbital and supratrochlear veins drain blood from the forehead and the angle of the mouth, respectively. These veins and arteries work together to ensure efficient blood return from the scalp and face to the heart.”

Note: From the nose to the scalp the toxin(s) travel throughout the body system to the heart.m INHALED TOXINS ARE A DANGER TO ONE’S WELL-BEING.

One thought on “Thoughts Beyond Choir of Cloistered Canaries (CoCC.16a)–Chlorpyrifos / Febreze Chemicals”